Many women experience some form of hormonal based symptoms across their lifetime ranging anywhere from mildly uncomfortable to severely debilitating. In fact, 50-80% of reproductive-aged women experience premenstrual syndrome (PMS), and 75% of women report mild to severe symptoms as they transition into menopause.

When learning about hormones, many realise that the delicate interplay of a woman’s cyclical hormone balance is more complex than originally thought. This inevitably means understanding and resolving a hormone-based condition can be tricky, and finding the underlying causes may prove elusive without help.

What Symptoms and Conditions Are We Talking About Here?

Any woman can experience the odd irregular cycle, slightly more ‘crampy’ than normal period, or a minor mood fluctuation in the latter couple of weeks of her cycle – however, experiencing a regular problem and/or discomfort, though common, is most definitely not normal and therefore should be assessed by a health professional so it can be resolved. Though female reproductive cycle issues can come in a range of shapes and sizes, some of the most common seen clinically are listed below:

- PMS: symptoms of fluid retention, breast tenderness, anxiety, depression and food cravings occurring in the two weeks before menstruation.

- Dysmenorrhoea: painful menstruation.

- Menorrhagia: heavy menstruation.

- Oligo-/Amenorrhoea: irregular or absent menstruation.

- Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS): often classified by the presence of cysts on the ovaries, elevated androgens, acne, hirsutism (excessive hair growth) and/or absence of ovulation

- Fibroids: benign growths within the uterine wall, commonly resulting in dysmenorrhoea and menorrhagia.

- Endometriosis: tissue that normally lines the uterus grows elsewhere (outside the uterus), resulting in dysmenorrhoea, pain during other times in the month and potentially infertility.

- Adenomyosis: tissue that normally lines the uterus grows into the inner layers of the uterus, resulting in dysmenorrhoea, menorrhagia, and infertility.

Whether the picture is mild or severe, the appearance of any of the above leads to the next logical question – what is it that causes these conditions to arise?

The Chorus, Not the Co-Stars

The simplest way to understand pretty much all female reproductive conditions is to begin with acknowledging that something has become unbalanced – but what does that actually mean, and should we be looking to the hormones themselves or not?

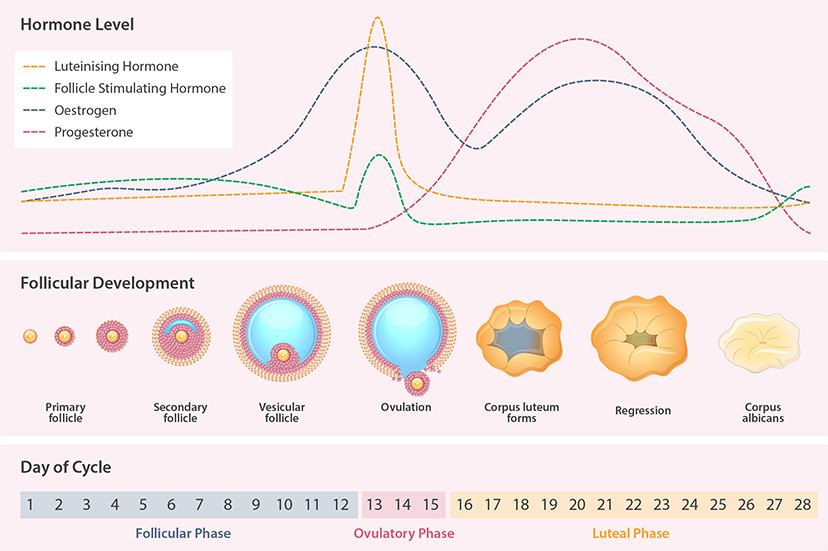

Let’s start with the two hormonal ‘leading ladies’ you are most likely to be familiar with: oestrogen and progesterone. These are two of the key players (along with follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone[LH]) in the cyclical, reproductive activities of the female body – rising and falling during the cycle and contributing to the maturation and release of an egg (ovulation), and the growth and development of the endometrium (uterine lining) to prepare for a potential pregnancy. Typically, if fertilisation does not occur following ovulation, production of these hormones drop away, triggering the onset of monthly menstruation, beginning the cycle all over again (see Figure 1).

Up until recently, many female hormonal disorders were viewed through the simplified lens of there being either too much or too little of these two hormones; therefore the strategy was to raise or lower their levels to ‘balance’ the cycle out again. For example, PMS and amenorrhoea were viewed as simply due to low progesterone; and dysmenorrhoea, endometriosis and fibroids caused by excess oestrogen production. Nowadays we understand it’s more accurate to gauge hormonal status by assessing the activity of a hormone rather than just testing to see what the levels might be – especially as testing hormones, in many instances, doesn’t reflect what’s actually going on inside the body.

That’s because there’s more to this hormonal tale than oestrogen and progesterone. You see, female hormonal health is also impacted by a whole troupe of other hormones and compounds. For example, thyroid hormone, insulin, androgens (e.g. testosterone) and cortisol all have the capacity to positively or negatively influence female reproductive health.

It’s a Growing Cast

Furthermore, the latest science now reveals female hormone activity is impacted by a number of additional processes, molecules and systems. For example:

- Inflammation: causes an increase in local tissue oestrogen production(meaning oestrogen produced in places other than in the ovaries), elevates androgens, increases insulin levels and causes decreased progesterone levels.

- Toxins, e.g. endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs): increase the oestrogenic load on the body, and are linked to abnormal puberty, irregular cycles, reduced fertility, PCOS, endometriosis, fibroids and early menopause.

- Mast cells: part of the immune system, these cells can be triggered by EDCs and oestrogen, releasing a flood of inflammatory cells and histamine in the pelvic cavity. Whilst traditionally associated with allergies, mast cells are a primary contributor to the marked inflammation and pain seen with endometriosis and adenomyosis.

- Gut dysbiosis: an imbalance of the normal, healthy microbial life residing within the gastrointestinal tract can reduce the efficiency of oestrogen detoxification and elimination, increasing the overall oestrogenic load. Dysbiosis has been linked with PCOS, endometriosis and fibroids. We now know that a healthy microbiome is also required to detoxify EDCs from the body.

- Brain changes: an increase in inflammation within the brain (caused by ongoing stress for example) alongside a reduction in neuroplasticity(the ability of brain structures to adapt well) is now known to play a role in PMS mood-based symptoms such as anxiety, irritability and depression.

Hormones: The Tip of the Iceberg

So as you can see, optimal female hormonal health and conditions such as PMS, PCOS or endometriosis are not merely the result of hormonal levels. Instead, it is dysfunction across the nervous, digestive, immune, and entire hormonal system that can cause the clinical presentations listed above. As such, the way to successfully treat these conditions is to identify the upstream triggers in order to resolve the downstream hormonal symptom manifestations.

What Are Your Triggers?

The web that creates hormonal imbalance is multi-layered, complex and highly individualised to each woman. Rather than trying to self-diagnose, enlist the help of a Natural Healthcare Practitioner. This can be invaluable, as they have the capacity to adeptly assess what contributing factors are at play in your unique situation based upon thorough case-taking and, in some cases, functional testing options. Their specialised knowledge allows them to craft a personalised treatment plan that will address not only your symptoms but begin to tackle the underlying causes of them. Investing in this approach to your care is a potent way to decrease the frustration of having to figure out your own hormonal puzzle, one of the most difficult in your body!

While your hormones play a key role in your current health, they aren’t the only contributor to your overall wellbeing. If it’s time to finally understand (and then resolve) the symptoms that have you feeling trapped, exasperated, and/or in pain each month, begin your journey towards a more balanced and vital body today.

References

Alpañés M, Fernández-Durán E, Escobar-Morreale HF. Androgens and polycystic ovary syndrome. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2012;7(1):91–102.

Baker JM, Al-Nakkash L, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Oestrogen-gut microbiome axis: physiological and clinical implications. Maturitas. 2017 Sep;103:45-53. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.06.025.

Bertone-Johnson ER. Chronic inflammation and premenstrual syndrome: a missing link found? J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016 Sep;25(9):857-8. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.5937.

Cubeddu A, Bucci F, Giannini A, Russo M, Daino D, Russo N, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor plasma variation during the different phases of the menstrual cycle in women with premenstrual syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011 May;36(4):523-30. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.08.006.

Claus SP, Guillou H, Ellero-Simatos S. The gut microbiota: a major player in the toxicity of environmental pollutants. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2016 May 4;2:16003. doi: 10.1038/npjbiofilms.2016.3.

Ezaki K, Motoyama H, Sasaki H. Immunohistologic localization of estrone sulfatase in uterine endometrium and adenomyosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Nov;98(5 Pt 1):815-9.

Gao L, Gu Y, Yin X. High serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016 Oct 20;11(10):e0164021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164021.

Gold EB, Wells C, Rasor MO. The association of inflammation with premenstrual symptoms. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016 Sep;25(9):865-74. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5529

Gore AC, Chappell VA, Fenton SE, Flaws JA, Nadal A, Prins GS, et al. Executive Summary to EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr Rev. 2015 Dec;36(6):593-602. doi: 10.1210/er.2015-1093.

Kirchhoff D, Kaulfuss S, Fuhrmann U, Maurer M, Zollner TM. Mast cells in endometriosis: guilty or innocent bystanders? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012 Mar;16(3):237-41. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.661415.

Loewendorf AI, Matynia A, Saribekyan H, Gross N, Csete M, Harrington M. Roads less travelled: sexual dimorphism and mast cell contributions to migraine pathology. Front Immunol. 2016;7:140. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00140.

Niswender GD, Juengel JL, Silva PJ, Rollyson MK, McIntush EW. Mechanisms controlling the function and life span of the corpus luteum. Physiol Rev. 2000 Jan;80(1):1-29.

Original article by Ruth Kirk-Garcia, from Metagenics and updated by Vital Health Naturopathy